japanese theatre i.b.m.

Japan, of course, is still East, but it’s not as far away as we think. Distances are shorter nowadays, and there are some ways of travel that are measured in time, not kilometres. Telecommunications and new technologies know no limits. Thanks to this, the East is nearer than ever.

That said, we still find it exotic, above all the parts of it we don’t know. It’s amazing the amount of people who are especially enthralled by Japan. Or maybe that should be the amount or people who are enraptured by the richness of character that abounds in this elegant country.

For instance, who doesn’t know of their Geishas? You can picture them in a moment: their colourful costumes, their over-the-top and attentioncalling make up, their very unique and special movements...

So far so good, at least as far as the reality offered by their soul or Japanese cinema.

But, and here’s a question for you, what do we know about Kabuki? Not many would even be able to guess what it was. Kabuki is a branch of Japanese Theatre. The geisha, the samurai and characters of their ilk, Japanese cinema and Western cinema (Sergei Eisenstein is a clear example of this) have all learned a lot from Kabuki, a lot more that they think.

Kabuki is the name given to a style of theatre born in the 16th Century.

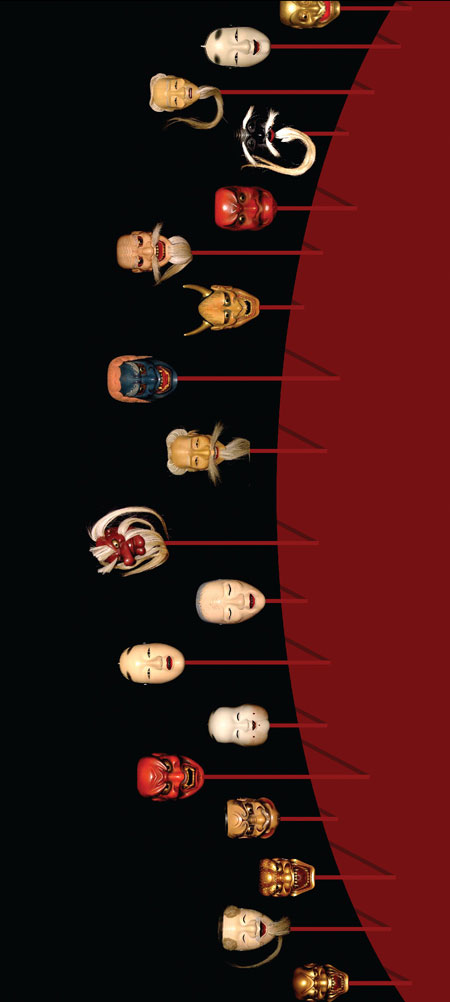

Kabuki basically originated out of Noh theatre. That’s not to say that Noh created it, it was basically started to make Noh more accessible to the public in general. Noh has a seven hundred history in its own right, but it has always been out of reach to the general public.

Kabuki, on the other hand, was created with the general public in mind and is now reaping the rewards of such a stance. It is a huge favourite with people.

Kabuki or its philosophy and physiognomy, are rather difficult to understand at first glance because of the fact that everything is based on unreality. This is especially so if we look at from a western perspective where we are accustomed to seeing theatre that reproduces reality on stage: the more real, the more natural; the more natural the better.

In Kabuki, however, they escape from reality. They get as far away from everyday life as possible, as far away from normal techniques and expressions as possible. You could say that they even have their own special language coded in symbolism.

Kabuki has to be appreciated as a whole. The sounds, movements, spaces and voices are all given the same importance. One’s not there to back up the other, there are no differences and each element is granted the same importance and presence. The group, in the true meaning of the word, makes up everything: the elements of harmony and inner energy make this type of drama crackle on a lively and colourful stage.

This is how Kabuki instinctively mesmerises the audience; it worms its way into peoples’ minds and it provokes. Kabuki, as well as achieving the aforementioned complicity so hard to come across, is also capable of making us hear movements and see sound. Don’t ask us what strength, perfection, harmony and monism they use to do so.

It’s is a different way of telling a story, yet it is a story: there’s drama, a start, an evolution and a finish. The same characters appear in every play. The type of characters in Kabuki are very set and the story is built around the different combinations of these characters: when they appear, when they disappear. Men have been the only actors in Kabuki for a long time now. This means that men also play the roles of the women characters whenever there is one. This makes more sense when we take into account that Kabuki is based on unreality. Whatever way you look at it, the professionalism of Kabuki actors is amazing, as is the way the deeply rooted and highly calculated Kabuki can enrapture an audience, without seeming to try and do so.

As a Kabuki actor once said: “If, on stage, I have to turn my back to the audience, I keep on acting. The inner movement never ceases, not inside me nor in my head, and the audience can appreciate this. If not, my back would just be getting in the way”.

The image of sap could just be the metaphor to use when thinking of Kabuki: it’s there, still and quiet, but not mute and, of course, it’s very much alive and strongly rooted to the ground.

That said, we still find it exotic, above all the parts of it we don’t know. It’s amazing the amount of people who are especially enthralled by Japan. Or maybe that should be the amount or people who are enraptured by the richness of character that abounds in this elegant country.

For instance, who doesn’t know of their Geishas? You can picture them in a moment: their colourful costumes, their over-the-top and attentioncalling make up, their very unique and special movements...

So far so good, at least as far as the reality offered by their soul or Japanese cinema.

But, and here’s a question for you, what do we know about Kabuki? Not many would even be able to guess what it was. Kabuki is a branch of Japanese Theatre. The geisha, the samurai and characters of their ilk, Japanese cinema and Western cinema (Sergei Eisenstein is a clear example of this) have all learned a lot from Kabuki, a lot more that they think.

Kabuki is the name given to a style of theatre born in the 16th Century.

Kabuki basically originated out of Noh theatre. That’s not to say that Noh created it, it was basically started to make Noh more accessible to the public in general. Noh has a seven hundred history in its own right, but it has always been out of reach to the general public.

Kabuki, on the other hand, was created with the general public in mind and is now reaping the rewards of such a stance. It is a huge favourite with people.

Kabuki or its philosophy and physiognomy, are rather difficult to understand at first glance because of the fact that everything is based on unreality. This is especially so if we look at from a western perspective where we are accustomed to seeing theatre that reproduces reality on stage: the more real, the more natural; the more natural the better.

In Kabuki, however, they escape from reality. They get as far away from everyday life as possible, as far away from normal techniques and expressions as possible. You could say that they even have their own special language coded in symbolism.

Kabuki has to be appreciated as a whole. The sounds, movements, spaces and voices are all given the same importance. One’s not there to back up the other, there are no differences and each element is granted the same importance and presence. The group, in the true meaning of the word, makes up everything: the elements of harmony and inner energy make this type of drama crackle on a lively and colourful stage.

This is how Kabuki instinctively mesmerises the audience; it worms its way into peoples’ minds and it provokes. Kabuki, as well as achieving the aforementioned complicity so hard to come across, is also capable of making us hear movements and see sound. Don’t ask us what strength, perfection, harmony and monism they use to do so.

It’s is a different way of telling a story, yet it is a story: there’s drama, a start, an evolution and a finish. The same characters appear in every play. The type of characters in Kabuki are very set and the story is built around the different combinations of these characters: when they appear, when they disappear. Men have been the only actors in Kabuki for a long time now. This means that men also play the roles of the women characters whenever there is one. This makes more sense when we take into account that Kabuki is based on unreality. Whatever way you look at it, the professionalism of Kabuki actors is amazing, as is the way the deeply rooted and highly calculated Kabuki can enrapture an audience, without seeming to try and do so.

As a Kabuki actor once said: “If, on stage, I have to turn my back to the audience, I keep on acting. The inner movement never ceases, not inside me nor in my head, and the audience can appreciate this. If not, my back would just be getting in the way”.

The image of sap could just be the metaphor to use when thinking of Kabuki: it’s there, still and quiet, but not mute and, of course, it’s very much alive and strongly rooted to the ground.