siberian education

This book that starts and ends in the war in Chechnya doesn’t speak about Chechnya. It speaks of a Siberian tribe. Of a tribe of honourable thieves to be precise. It speaks of a proud people who follow their own laws. Of a society that was still alive up to 20 years ago. It’s told in the first person. Told by a member of that tribe of honourable thieves. By the koltsik or tattooist Nicolai Lilin to be precise. This story that starts and ends in Chechnya painfully brings to the surface – just like a tattoo – a secret passage of Soviet Union history. Though born (1980) in the city of Bender in the Transnistria Republic (pro-independence Moldavian territory) Bender Nicolai Lilin is a Siberian, from the Urka tribe. It’s well documented that Stalin sent whole villages and peoples to Siberia, but it’s lesser known that he emptied territories in Siberia and dispersed the people all over the Soviet Union. The Urka community was split up and sent to different places. However, though they had been taken from their homelands, the Urkas had no intention of changing their way of life. This attitude caused problems for them with their new neighbours. Lilin speaks of his childhood and opens up this closed off world to us. Through his teenage eyes we discover the traditions and way of life of these honourable thieves. The importance of traditions and rites that must be respected even in the smallest elements of everyday life. We are all witnesses, the Urkas would never permit the exclusion of their children from their life of crime.

The most important moment in the life of an Urka adolescent is when an adult gives them a knife called a pika. This knife turns them into adults and criminals. For this people who engaged in criminal activity on a daily basis, it was quite common for them to become involved in knife fights with other law-breakers, for them to kill police officers or to go to prison. Prison is one harsh reality that all Urkas are familiar with. Lilin describes in all its crudeness the raping and murder that takes place in the juvenile prisons where the youngest inmates are kept. In prison, the Urkas were a closed community with their own laws and hierarchy. With their strict self-imposed rules in prison (no drugs, no sex and no contact with the police), the Urkas, like a pack of wolves, defined themselves as being ¨honourable thieves¨.

However, the book is not all violence, though violence is always present in the lives of this Siberian tribe in exile. Lilin also describes many traditions of his people , their festivals, rituals and their beliefs, generally connected to some form of weapon. It’s also a book dedicated to a Siberian education, kinship, nature transformed by man and the disappearance of innocence. In Italy, they have compared him to Roberto Saviano. That seems, to us, to be more of a thing by the publishers and journalists. Marketing, in a word. Saviano wrote about the Gomorra as a journalist and witness. Lilin, writes from the viewpoint of someone who has that life tattooed onto his skin.

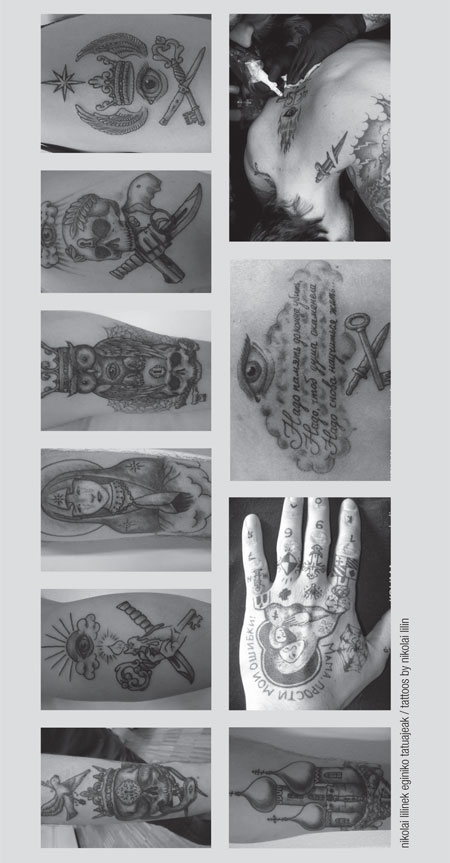

skin talking

Tattoos are very important for the Urkas. The tattoos speak volumes. Nobody can just go ahead and engrave whatever they like into their skin. Each drawing, each word has a different complex meaning, only understandable to one who knows how to read them. Nicolai was attracted to tattoos from childhood. He learned the techniques of drawing on skin and became a koltsik. It was forbidden in the Soviet Union because they knew there were secret codes used. For instance, the message in the tattoos of the leader of the Russian mafia group “Black Seed” have become well known. Cats, towers, spiders… the code has become common knowledge and has thus lost any sense of meaning. The Urkas will never reveal the meaning of a tattoo to someone who doesn’t need to know. The tattoo artist becomes the sender of a message and encryptor and that bestows special status on this figure within the tribe. Nicolai Lilin was sent to the war in Chechnya when he was 19 years old (he writes of his experiences there in his latest book Caduta Libera, which has yet to reach these shores). When he finished military service, he headed to Italy. He lives there now, where he this skin scribe occasionally writes on paper.

The most important moment in the life of an Urka adolescent is when an adult gives them a knife called a pika. This knife turns them into adults and criminals. For this people who engaged in criminal activity on a daily basis, it was quite common for them to become involved in knife fights with other law-breakers, for them to kill police officers or to go to prison. Prison is one harsh reality that all Urkas are familiar with. Lilin describes in all its crudeness the raping and murder that takes place in the juvenile prisons where the youngest inmates are kept. In prison, the Urkas were a closed community with their own laws and hierarchy. With their strict self-imposed rules in prison (no drugs, no sex and no contact with the police), the Urkas, like a pack of wolves, defined themselves as being ¨honourable thieves¨.

However, the book is not all violence, though violence is always present in the lives of this Siberian tribe in exile. Lilin also describes many traditions of his people , their festivals, rituals and their beliefs, generally connected to some form of weapon. It’s also a book dedicated to a Siberian education, kinship, nature transformed by man and the disappearance of innocence. In Italy, they have compared him to Roberto Saviano. That seems, to us, to be more of a thing by the publishers and journalists. Marketing, in a word. Saviano wrote about the Gomorra as a journalist and witness. Lilin, writes from the viewpoint of someone who has that life tattooed onto his skin.

skin talking

Tattoos are very important for the Urkas. The tattoos speak volumes. Nobody can just go ahead and engrave whatever they like into their skin. Each drawing, each word has a different complex meaning, only understandable to one who knows how to read them. Nicolai was attracted to tattoos from childhood. He learned the techniques of drawing on skin and became a koltsik. It was forbidden in the Soviet Union because they knew there were secret codes used. For instance, the message in the tattoos of the leader of the Russian mafia group “Black Seed” have become well known. Cats, towers, spiders… the code has become common knowledge and has thus lost any sense of meaning. The Urkas will never reveal the meaning of a tattoo to someone who doesn’t need to know. The tattoo artist becomes the sender of a message and encryptor and that bestows special status on this figure within the tribe. Nicolai Lilin was sent to the war in Chechnya when he was 19 years old (he writes of his experiences there in his latest book Caduta Libera, which has yet to reach these shores). When he finished military service, he headed to Italy. He lives there now, where he this skin scribe occasionally writes on paper.