tativille

Jaque s Tati was born i n 1907 and died in 1982. He developed a cinematic point of view which will always be linked with his name.

When he was young he worked in musicals and mime.

What he saw and learned at the time was to influence his whole artistic career. His films are a bridge between silent movies and modern cinema. On the one hand his films combine silent movies’ innocence and cinema narrative and, on the other hand, an ironic and sharp criticism of

the influence of post-World War 2 industrialisation on society. He did this all, with hardly any words used, by combining characters, objects and scenery with perfect

choreography.

In 1958 Tati’s Mon Oncle won two prizes: the Oscar for the best non-English language film and main prize at Cannes. Thanks to that success, he was able to start filming his long-time dream: Playtime. Before starting on this new film, Tati visited the capital cities of Europe to study the

modernist architecture. His initial idea was to locate the film in several locations in Paris, but he wasn’t happy with the tests. When he heard he wasn’t going to be given permission to film at Orly airport, he decided to go for another option.

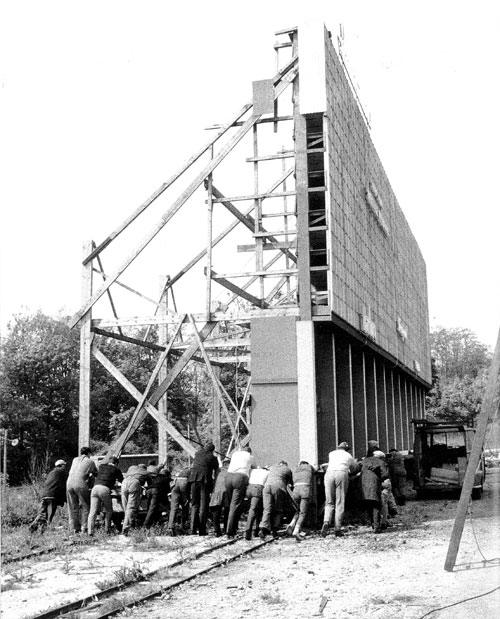

It wasn’t easy work. It was a very ambitious film and even though it had a big budget (17 million francs), he ran out of money more than once during filming. The main problem: Tativille. Tativille was the town he built at Gravelle, a

15,000 metre area on the outskirts of Paris. During the three years it took to make the film (from 1964 to 1967), there were numerous problems with the production. Amongst other things, a storm destroyed many parts of Tativille. In order to carry on filming, they used giant photographs

and, thanks to the effects of trompe l’oeil, they managed to rebuilt Tativille in record time. They went way over the original budget and, in order to finish the film, Tati had to sell his own house and president Pompidou ordered him to be given a special loan. When asked about the fortune

he had spent to build Tativille, Tati said: “Building Tativille has cost as much as hiring Liz Taylor would have. We all have our own priorities”.

The main character in Playtime is Monsieur Hulot, once more played be Tati himself. The film has six parts: the airport, offices, an exhibition of inventions, apartments with glass walls, a park and an automatic merry-g oround. In those places we see what Monsieu Hulot and some recently arrived American tourists get up to, and this is a pretext for seeing how the city is influenced by

its surroundings. Tati shows us all of this with his usual image and sound tricks. In a sophisticated and ironic way he criticises modern society and its way of building cities. At the start of Playtime people follow the patterns laid down by architects. They respect the lines and spaces created by the buildings as if they were prisoners. The architecture itself is the film’s main focus and it influences the characters’ behaviour directly. But, little by little, the architecture’s exact lines are softened and people begin to form closer relationships, and at the end it’s as if there were no straight lines at all.

Tati ref lects on cities’ roles in Playtime. Life, work, transport, leisure ... Although it’s paradoxical, Tati, who was so critical of the cities which modern society was creating, was also very keen on those cities’ architecture and wanted to know all about it. He shows cities’ dehumanisation, on the one hand, but, on the other, you also see his fascination with contemporary architecture and design. It’s something that comes up in all his films. You only have to remember the modernist house in Mon Oncle, Villa Arpel: geometry, colours, plastic, an automatic garage, the garden path, the kitchen laboratory, the tap which looks like a fish... On the one hand, it’s a criticism of the idea of minimalism and clean lines. On the other, the ludic possibilities which that foolishness offers you.

Playtime was praised by the critics but ignored by the public. It was a huge flop and, although he tried, Tati did not manage to save Tativille. André Malraux (the egocentric writer and French minister of culture at the time) ordered Tativille’s demolition. On reflection, it was the biggest favour they ever did Tati. From now on, if anyone wants to see the most modern city in old Europe in the middle of the last century, they’ll have to watch Playtime.

When he was young he worked in musicals and mime.

What he saw and learned at the time was to influence his whole artistic career. His films are a bridge between silent movies and modern cinema. On the one hand his films combine silent movies’ innocence and cinema narrative and, on the other hand, an ironic and sharp criticism of

the influence of post-World War 2 industrialisation on society. He did this all, with hardly any words used, by combining characters, objects and scenery with perfect

choreography.

In 1958 Tati’s Mon Oncle won two prizes: the Oscar for the best non-English language film and main prize at Cannes. Thanks to that success, he was able to start filming his long-time dream: Playtime. Before starting on this new film, Tati visited the capital cities of Europe to study the

modernist architecture. His initial idea was to locate the film in several locations in Paris, but he wasn’t happy with the tests. When he heard he wasn’t going to be given permission to film at Orly airport, he decided to go for another option.

It wasn’t easy work. It was a very ambitious film and even though it had a big budget (17 million francs), he ran out of money more than once during filming. The main problem: Tativille. Tativille was the town he built at Gravelle, a

15,000 metre area on the outskirts of Paris. During the three years it took to make the film (from 1964 to 1967), there were numerous problems with the production. Amongst other things, a storm destroyed many parts of Tativille. In order to carry on filming, they used giant photographs

and, thanks to the effects of trompe l’oeil, they managed to rebuilt Tativille in record time. They went way over the original budget and, in order to finish the film, Tati had to sell his own house and president Pompidou ordered him to be given a special loan. When asked about the fortune

he had spent to build Tativille, Tati said: “Building Tativille has cost as much as hiring Liz Taylor would have. We all have our own priorities”.

The main character in Playtime is Monsieur Hulot, once more played be Tati himself. The film has six parts: the airport, offices, an exhibition of inventions, apartments with glass walls, a park and an automatic merry-g oround. In those places we see what Monsieu Hulot and some recently arrived American tourists get up to, and this is a pretext for seeing how the city is influenced by

its surroundings. Tati shows us all of this with his usual image and sound tricks. In a sophisticated and ironic way he criticises modern society and its way of building cities. At the start of Playtime people follow the patterns laid down by architects. They respect the lines and spaces created by the buildings as if they were prisoners. The architecture itself is the film’s main focus and it influences the characters’ behaviour directly. But, little by little, the architecture’s exact lines are softened and people begin to form closer relationships, and at the end it’s as if there were no straight lines at all.

Tati ref lects on cities’ roles in Playtime. Life, work, transport, leisure ... Although it’s paradoxical, Tati, who was so critical of the cities which modern society was creating, was also very keen on those cities’ architecture and wanted to know all about it. He shows cities’ dehumanisation, on the one hand, but, on the other, you also see his fascination with contemporary architecture and design. It’s something that comes up in all his films. You only have to remember the modernist house in Mon Oncle, Villa Arpel: geometry, colours, plastic, an automatic garage, the garden path, the kitchen laboratory, the tap which looks like a fish... On the one hand, it’s a criticism of the idea of minimalism and clean lines. On the other, the ludic possibilities which that foolishness offers you.

Playtime was praised by the critics but ignored by the public. It was a huge flop and, although he tried, Tati did not manage to save Tativille. André Malraux (the egocentric writer and French minister of culture at the time) ordered Tativille’s demolition. On reflection, it was the biggest favour they ever did Tati. From now on, if anyone wants to see the most modern city in old Europe in the middle of the last century, they’ll have to watch Playtime.